Crisis Averted : Rescuing Apollo 11

The Apollo 11 mission's guidance computer repeatedly flashed the error code 1202 while Armstrong and his crew were making their landing approach. What happened next?

This article is the first in a two part series about how the Apollo 11 and Apollo 14 missions suffered serious setbacks in their computers which were fixed on the fly, allowing both missions to proceed without further mishaps.

|

|---|

| Source: NASA |

After a decade of training, the time had come. The Apollo 11 mission would be the first time man set foot on the moon. The weight of a planet rested on the shoulders of three men - Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. Much like the pilots of airplanes, the module was also on autopilot for most of the journey. The trusty computer had taken them over three hundred thousand kilometers of nothingness. After four days of being stuck in a capsule with no one else, they were reaching their destination. Armstrong and Aldrin now switched seats for the next part of the plan, while Collins would remain in the orbiter. Their lunar descent module detached from the orbiter just over a hundred kilometers from the surface of the moon. Again, it was the refrigerator-sized box with less power than a cell phone that would be responsible for putting Homo sapiens on the moon. Or would it?

You’re still orbiting the planet, so the first task to descend would be to kill your horizontal velocity to a more controllable number. You push the buttons to initiate the descent procedure, and your computer kicks into action. It’s time to run the PDI routine. The engine starts slowing you down, and you’re good. The computer throws in code 500 - the antenna was out of position. It seems to be fine; you check it anyway and clear the warning.

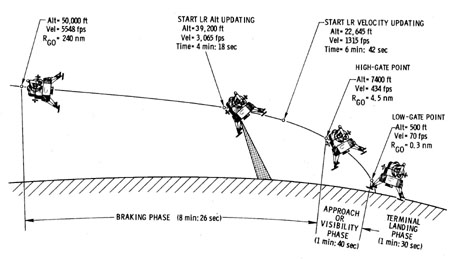

|

|---|

| Phases of the Lunar Landing1 |

You’re no longer orbiting. You will be hurtling towards the surface of a rocky, dusty world. Landings require a massive effort from the pilots to put the craft safely on the ground. Luckily for you, you are among the best, and you’re watching over this silicon circuitry to place you down. The chip works down the BURNBABY routine. The propellant flowed, the engine fired.

You need to know your position and velocity to make a safe landing on the lunar surface. This part is straightforward, the radar gives you the data. Both yourself and mission control approve it, and you can carry on. You ask the computer to calculate the height difference between the computed and actual altitude. VERB 16 NOUN 68. It tells you that the error is 2900 feet, which is reasonable. What was not reasonable is the ringing in your earpiece. Not good.

What could the error possibly be? You try to switch the screens to find out. VERB 5 NOUN 9.

“It’s a 1202. What is that? Give us a reading on the 1202 Program Alarm.” You have numerous hours of training for multiple scenarios that could have happened on the mission. Neither you nor the commander, Neil Armstrong, have an inkling about what this error means.

30 long seconds pass. Mission control gets back to you saying it’s all good, make the landing. Ok, maybe that was a non-event. Let’s get the difference again. 900 feet. Should be good? Not so fast! The computer crashes again with the same error code. Mission Control gives the go signal again. You’ve dropped six kilometers in this craziness. You’ve been trained to remain calm, and so you will.

600 meters from the surface. A 1201 alarm. 24 more seconds. A 1202 alarm. Mission control seems nonchalant about this and lets you proceed. 16 more seconds. Another 1202.

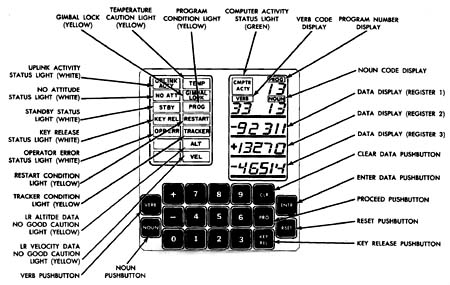

|

|---|

| An overview of the landing site2 |

Your commander has had enough. This man has fought for the Navy in Korea. He’s rescued the Gemini 8 while it was spinning in space. He switched the autopilot into ATT HOLD, which instructed to computer to hold elevation while he would pilot the craft manually. This eased up on the computational load and no more alarms sounded. Up close, the surface was a mess. Rubble on the ground would mean the landing might be harsh… Nope. Armstrong put the vehicle on the dust, kicking it up. A tiny bounce and your craft lands safely on the ground, to a perfect halt. The agony was done.

Far from it. Many miles away, MIT housed the brains behind the Apollo Guidance Computer. Hal Lanning was the mastermind behind the programming paradigm for the Apollo computer. Multiple processes would have to be simultaneously run, but there was a single processor available. Laning hacked his way around this by assigning every job a priority number. Guidance and control of the craft would be low priority processes always in the background, while requests by astronauts would be the higher priority ones. With the paradigm in their hands, the responsibility of programming fell to Charles Muntz. He determined that there was a possibility that when flooded with commands, the system might get overwhelmed. To prevent adverse effects, the computer would then save a copy of everything going on right then in a checkpoint of sorts and restart. On returning to life, it only reopens essential processes. The processes themselves, consisted of VERBs and NOUNs, to tell the computer what to do. VERBs, much like English, were action commands while NOUNs requested a specific token.

|

|---|

| Lunar Module Display and Keyboard Unit (DSKY)1 |

If a copy of variables had to be saved when a higher priority process had to be run, the executive function allotted some space. Vector and matrix calculations need a lot of space, so the lunar guidance computer housed five vector accumulator areas (VACs). The highly restricted amount of computational power meant upto eight jobs could stay in the queue at any point of time and only five of them could use the VACs. The backup system when this system gets overwhelmed is highly necessary to prevent disaster. If the executive function ran out of slots in the queue, then it issued error code 1202, while it issued 1201 when it ran out of VAC slots. It would then run BAILOUT, which would restart the system.

Don Eyles was the man who worked on programming the final descent. To him, this situation was never good. The guidance used 87% of computation until this moment while Aldrin’s request added another 3%. The remaining computation power was being used by a mystery process. As the craft approached the surface, guidance would want more computation power, and the process wouldn’t give up the space causing the system to crash multiple times.

Back on Earth, the MIT team found the mystery process. The Lunar Module which made its way to the surface would eventually have to go back and link up with the Command Module in orbit with Collins. The instrument responsible for getting them to meet was the rendezvous radar. This radar would measure the range and range-rate of the other craft and was also backed up when the abort guidance system kicked in. The radar was hooked into the attitude control system. This system was frequency-locked with the guidance computer which was good. But the signals were out of phase because the guidance computer powered up after the control system. The unit coupling the data from the radar with the guidance computer began to increment and decrement counters in the guidance computer when it got contradicting signals which was the mystery process eating up the CPU. Armstrong and Aldrin switched the mode of the radar to the right position and blasted off into lunar orbit. Three days later, they splashed down on the Pacific and the rest is history.

|

|---|

| Splashdown! Image from Flickr |

-

Image from the Lunar and Planetary Institute ↩