Crisis Averted : Rescuing Apollo 14

An errant ball of solder completed the abort circuit of the Apollo 14 landing before it even attempted to do so. Could the mission be rescued with barely any time to spare?

This is the other article in the two part series about how the Apollo 11 and Apollo 14 missions suffered serious setbacks in their computers which were fixed on the fly, allowing both missions to proceed without further mishaps.

|

|---|

| Source: NASA |

The roaring success of Apollo 11 and the relatively quieter success of Apollo 12 was followed by the disastrous Apollo 13 mission. In an absolutely nerve-racking mission, the lunar landing was aborted after an explosion in an oxygen tank depleted the available resources. With limited water and power and low heating, the crew transferred all remaining resources into the lunar module and used it to re-enter Earth. Despite being an arguably more daring rescue, it all came down to a relatively tame problem - faulty wiring. NASA implemented design changes and added backup resources to ensure better safety for their next mission, along with some software updates. Eager to prove that they still had their touch, they launched the Apollo 14 mission with high hopes. Chosen to lead the mission was veteran astronaut Alan Shepard Jr. At 47 years of age and fresh from ear surgery, he was keen to lead the mission and to see the crew all the way.

Soon after the trans-lunar injection, a problem cropped up, jeopardizing the entire mission. The command module, Kitty Hawk could not dock with the lunar module, Antares. After repeated efforts from the astronauts, they finally fixed the mechanical issue and shot it off to the Selene. However, four hours before the landing, there was a new problem. The consoles at Mission Control indicated that the abort button had been pressed. They radioed back to the module, which replied in the negative - no one had pushed the button. To make sure that the button was pressed from the other end as well, Houston radioed the crew to pull up the display of the I/O channel. They keyed in VERB 11; NOUN 10; 30 on the display keyboard (DSKY), which on translating from computer to humanspeak would mean “show me the octal data; from the I/O channel; for the status bits”. Among the status bits, the final bit represented Abort with descent stage and the value read 1.

|

|---|

| The DSKY for the Apollo Guidance Computer1 |

This was a serious problem. While the computer would not do anything amiss for now, there was danger in store. When the lunar module begins its descent procedure, Program 63, the computer will notice that the abort button was pushed and immediately abort the landing by calling Program 70 or Program 71. Resetting the value of the abort bit manually was not an option as it would have to be done multiple times in case it glitched up again during landing. Moreover, the astronauts had other commands to key in, and there was only a single panel. Once again, we go back to the Draper Lab at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. The geniuses at these desks had designed the code for this mission as well. The weight of the mission once again fell on the shoulders of our good friend from last time, Donald Eyles.

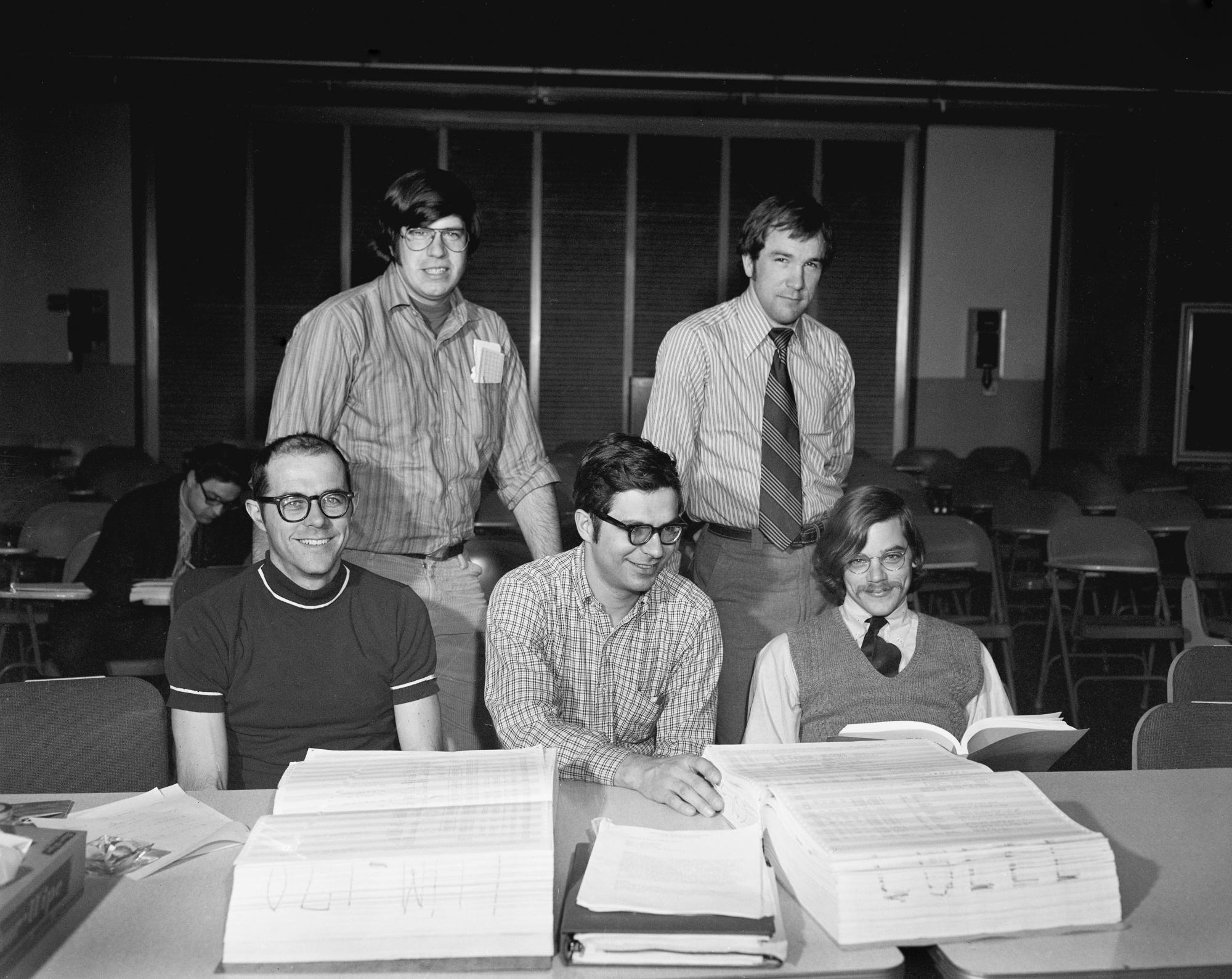

|

|---|

| The team at Draper Lab2 |

The first thing you do when your system glitches up is to rage at it. The second thing you do is to look around and pat it. This was exactly what the astronauts did. Tapping the panel around the abort switch cleared the abort bit. The orbiter now made its way to the far side of the moon, allowing the scientists on the ground to ponder how to fix it while the crew continued their tapping experiments. Just like the previous mission, it appeared that some faulty wiring or a metal bit like a ball of solder was making the circuit for the abort switch, turning it on. Just under an hour later, as the module regained comms with Mission Control, they confirmed that while tapping does help, they would need to be tapping other buttons soon enough. The irksome abort switch was still set to 1.

Eyles radioed a potential fix back to the crew, the command:

VERB 25; NOUN 7; 105; 400; 0. This loads data into the display registers and lets the computer know that crew will be changing bits manually. 105 and 400 localized the LETABBIT, which would show the state of the abort bit to other programs. The last argument sets this LETABBIT to 0. However, this was not a solid fix. The problems were obvious even to Eyles - the engine firing could always flip the abort bit again, rendering everything useless. The bigger problem was that in case a genuine abort was needed for the mission, the astronauts would not be able to launch the procedure leaving their fates uncertain.

Antares vanished behind the dark side of the moon for its final orbit before landing.

To proceed further, let’s break down the landing procedure a bit more. P63, the landing program, receives acceleration and attitude values from the SERVICER job. This job, in turn, schedules Routine 11 as a waitlist task running four times every second. R11 checks the LETABBIT to see if aborts were allowed and then checks the abort signal. If it is enabled, P63 is killed, and P70 takes over control of the flight.

Eyles found a tiny bit of trickery in the code for R11. After checking the abort signal, R11 also performed a check to see if P70 was already running. It did this check by looking at the major mode number (MODREG) stored in the PROG field. This was simply a visual reference for the astronauts and could be changed to leave P63 running. It did leave two other problems, which were relatively not so mission breaking. The first was that the descent engine’s power gets set to a low value when the abort bit was on. This could be resolved by manually going full throttle. The second problem was that when the abort program was running (or appeared to be running), the ZOOMBIT, which triggers the guidance equations to calculate vital parameters for descent, would not be set. This would also have to be manually set via the DSKY.

With the fix in hand, Eyles radioed the crew with the updated fix. The first command to trick the computer would be to enter:

VERB 21; NOUN 1; 1010; 107

The first bit is a command to load the data into the registers followed by the address of the MODREG variable. Finally, 107 (71 in octal), tells the system to put P71 up on the display board. P71, which also controlled the abort procedures was put up so that P70 could be used in case an actual abort became necessary. Now, Shepard increased the manual throttle to full power. Next, the crew had to key in:

VERB 25; NOUN 7; 101; 200; 1

This bit sets the ZOOMBIT to 1. The command to set the LETABBIT to 0 from above would now have to be rerun. Finally, the MODREG would need to be reset to run P63 which only needs a minor change to the command which tricked the system:

VERB 21; NOUN 1; 1010; 77

Back under the control of the guidance computer, Shepard lowered the throttle and let the computer do its magic. Eight minutes later, the Apollo 14 safely touched down on the Fra Mauro highlands (with a tiny radar glitch in between causing a minor scare). Another successful mission added another feather to NASA’s cap as Apollo 14’s crew safely splashed down in the Pacific three days later.

|

|---|

| Touchdown! Source: NASA |